The Challenges of Forest Law Enforcement

While many tropical forest countries have strengthened their legal frameworks over the past decade, improvements in law enforcement have lagged behind, write Barbara Hermann, Haseeb Bakhtary and Darragh Conway from Climate Focus.

Important legal, policy and institutional reforms, often adopted as part of efforts to address illegal deforestation and manage forests more sustainably, have provided countries with the tools they need to align forest conservation and development goals. However, limited law enforcement budgets, corruption and a lack of political will are preventing these tools from being effectively applied.

So far, an uncoordinated approach to enforcement has led to duplicated efforts, wasted resources, bureaucratic manoeuvring and delayed detection and response to illegalities according to the UN Environment Programme. Some countries still do not have an inter-ministerial system or taskforce in place to coordinate enforcement efforts while others have developed such systems in the past decade with varying degrees of success.

In countries that have adopted such systems, broad and consistent engagement among relevant authorities is still lacking. However, there are instances where effective collaboration has been established among government agencies. In Indonesia, for example, the Directorate-General on Law Enforcement for Environment and Forestry (GAKKUM) was established to coordinate efforts with the police, attorney general’s office, the judiciary and customs.

Similarly, in Brazil, the Federal Public Prosecution Office has launched the programme ‘Amazonia Protege’ for governmental enforcement agencies to coordinate with scientific institutions and universities to use satellite data to more rapidly detect illegal activities. The Prosecution Office has also teamed up with the federal police, the main governmental body tasked with forest law enforcement (IBAMA) and the National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI) in recent years to conduct sting operations.

In Ghana, too, there have been some indications that coordination on enforcement between the attorney general, the Rapid Response Unit and the police has improved in recent years with the country also recently increasing penalties for forest offences.

Collaborating with civil society is also important for ensuring better enforcement of forest laws. In Indonesia, the role of civil society as an independent monitor of the timber legality assurance system has been formally recognized and their reports have resulted in administrative measures against companies.

Likewise, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, civil society analysis of geographical information systems data and alerts sent by community informants are increasingly being used by forest officials who lack the necessary investigative tools for detecting illegalities. However, elsewhere, the story has evolved differently and a growing number of countries have restricted the involvement and funding of non-governmental organizations in conducting environmental monitoring and reporting.

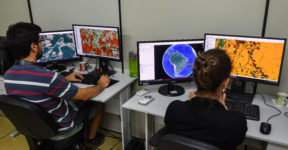

Satellite imagery and remote sensing technologies have facilitated forest monitoring and the detection of deforestation. In most countries, the use of remote sensing has been limited to forest management planning and forest cover change. However, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brazil use remote sensing systems and satellite imagery to classify land cover and identify deforestation and illegal logging.

Brazil has the most advanced system: enforcement units rely on sophisticated rapid-response satellite systems that can detect and locate large-scale deforestation in near real time, enabling enforcement units to react quickly to detected illegalities.

Timber tracking systems are also crucial tools for helping to detect potential illegalities. Many countries have invested in computerized systems thereby making timber less vulnerable to tampering and increasing efficiency for enforcement officials.

These investments have often taken place in the framework of Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) with the European Union. However, many countries continue to rely on paper-based systems which are difficult to oversee and audit and in which data and records are easily compromised.

Limited budgets for forest sector enforcement, as well as budget cuts, affect enforcement efforts in many countries. In Brazil, for example, the Ministry of Environment’s discretionary budget was cut by 43 per cent in 2017 while, in the Republic of the Congo, less than half of funding budgeted for forest enforcement was actually allocated to forest operations between 2014 and 2015.

Similarly, while the Indonesian government has prioritized anti-corruption and broader law enforcement in the forest sector with an increase in resources, budgets remain small in relation to the size of forests. GAKKUM had an annual budget that equalled 13 US cents per hectare of forest between 2015 and 2017 and the country’s Corruption Eradication Commission has seen its budget decrease in recent years.

The key reason for this is that enforcement teams are often insufficiently trained and resourced. In the Java-Bali-Nusa Tenggara region in Indonesia, for example, one police officer patrols 60,000 hectares of forest, while in Papua New Guinea, one officer covers half a million hectares.

Brazil and Cameroon have similar situations: in Brazil, 47 enforcement agents covered the entire Amazon region in 2014, while in Cameroon, one forest official covers 176,000 hectares of forest.

Limited resources and training also affect courts: judges and prosecutors receive limited – if any – training on forest matters and are often not up-to-date with forest laws.

Low wages, inadequate capacity and insufficient training provide an enabling environment for corruption and abuse of power as well as for the pursuit of informal sources of personal revenue.

Despite some improvements in efforts to curb corruption, it remains a significant hurdle across most tropical countries. While many countries have put anti-corruption agencies in place and introduced penalties for government officials, private companies and individuals who perpetrate corruption, it remains widespread among forest officials, within the judicial system and in the private sector.

Corruption is reinforced – and at times driven – by private sector interests. Companies sometimes try to obtain licences and concessions without following the required legal procedures. They may offer bribes to law enforcement authorities in return for turning a blind eye to illegal logging activities and seek preferential treatment by funding local politicians and helping them win elections.

Corruption among forest officials and in courts contributes to few cases coming to trial – and even fewer resulting in penalties, sanctions or convictions. In Cameroon, for example, forest officials commonly use ‘transactions’ and ‘amicable arrangements’ – informal practices that resemble bribes – instead of imposing fines and pursuing judicial prosecution. When companies believe that violations will not be detected, prosecuted or punished, they are more likely to act illicitly. In this sense, weak forest institutions foster noncompliance.

Leaders who show a firm commitment to implementing environmental laws have a positive influence on law enforcement. In contrast, it is often the case that a lack of political will to enforce environmental laws, propelled by the notion that environmental policy impedes economic development, leads to environmental ministries being marginalized and underfunded.

This is reflected in recent findings from Climate Focus and Chatham House which reveal that heads of government who have adopted policies and reinforced their commitment to transparent law enforcement, capacity-building and the independence of anti-corruption commissions, influenced forest stewardship positively. In contrast, those that did not, and those that used anti-environmental rhetoric, hampered progress.

In Laos, for example, enforcement actions have intensified and the country has seen a reduction in illegal logging following the issuance of an order by the Prime Minister in 2016.

A similar story unfolded in Malaysia in 2018 when a regime change saw a new government coalition in power that pledged to fight corruption. In the same year, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission conducted raids on the Sabah Forest Department and on timber companies; and the former chief minister of Sabah was charged with 46 corruption and money laundering counts in connection with timber concession contracts.

However, politicians from the previous Malaysian government returned to power in a new coalition in 2020 and, only three months following their return to power, the former chief minister was acquitted of all 46 charges. In a separate case, the stepson of the former prime minister was acquitted of money laundering charges of $248 million. These recent acquittals cast a shadow of doubt over the new coalition’s willingness to fight corruption.

In Brazil, the anti-environment rhetoric of the current president, as well as policies lobbied for by large landholders and adopted by the government since its election, have weakened environment protection laws and their enforcement which has ultimately led to a spike in deforestation. The Brazilian example also shows how discourse at the highest political level can influence behaviour locally: those at the deforestation frontier are more easily influenced by remarks made by the Brazilian president than the publication of decrees and laws in the government’s official gazette.

Law enforcement is key to reducing deforestation. In the past decade, tropical countries have improved coordination and increased the use of monitoring tools but a lack of political will and investment, coupled with continuously high levels of corruption, remain major challenges to forest enforcement. The following three areas for action should be prioritized to address these:

- Forest law enforcement needs to be included in the political agenda as a fundamental element to combating deforestation. While 93 countries have included forest-related greenhouse gas mitigation commitments in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), few have recognized improving forest governance and enhancing enforcement of forest regulations as necessary steps to decreasing deforestation. Governments are due to submit more ambitious NDCs by the end of 2020. It remains unclear whether they will submit tougher climate plans as their national priorities shift in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the renewal of NDCs would give countries an opportunity to better recognize the mitigation potential and cost-effectiveness of forest stewardship while also enhancing their commitment to better forest governance and enforcement.

- Increased funding is needed for all aspects of enforcement: from investigation to prosecution.Underfunded ministries, limited resources and capacities at forest units and insufficient training for government bodies are significant obstacles to enforcement and enablers for corruption – even when political will and coordination are present. Staff shape the institutions they work for and capacity gaps can erode confidence in institutions and undermine decision-making. It is, therefore, important that governments allocate sufficient resources to equip relevant authorities with adequate resources and capacity to accomplish their tasks.

- Given budgetary challenges in tropical countries, foreign donors can play an important role in providing financial and technical assistance for enforcement efforts. In the case of remote sensing technology, for instance, foreign institutions have been important players in developing local capacities. Most of the technology used for remote sensing in the countries studied was developed by, or with the support of, foreign agencies. For instance, the World Resource Institute developed the Interactive Forest Atlas and the Open Timber Portal in the Republic of the Congo and Cameroon in collaboration with the respective governments while the Japanese Cooperation Agency supported the forestry authority in Papua New Guinea to develop their system of remote sensing. The VPA frameworks, supported by the EU, also have played an important role in improving the technology used for timber tracking systems in some countries.

The latest figures on green finance reveal that, globally, less than 1.5 per cent of the $256 billion committed from 2010-17 to climate change mitigation – only $3.2 billion – reached efforts to protect forests in tropical forest countries. Another study indicates that only 0.12 per cent of climate research funding between 1990 and 2018 was allocated to the social science of climate mitigation – an area which includes the legal, political and social factors that determine the success of efforts to reduce emissions.

It is not clear how much funding is flowing into improving forest enforcement but it is certainly far less than the scale and urgency of the challenge demand. The underfunding of social science research may reveal a lack of global attention to the role governance, policy and law enforcement play in forest protection. More funding is therefore needed to elucidate the challenges and drivers of forest illegalities as well as to improve enforcement efforts on the ground. In particular, investment in monitoring tools and training for those involved in forest enforcement is necessary to improve the capacity of countries to prevent, detect and respond to forest illegalities.

This article is based on research conducted by Chatham House and Climate Focus in nine tropical countries: Brazil, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and the Republic of the Congo.