The Use of Open Data to Tackle Illegal Logging in Brazil

Civil society is making the most of current data to expose the extent of illegal logging in Brazil, but greater openness and collaboration could combat the illegal trade while advancing sustainable forestry, argues Renato Morgado of Transparency International.

In recent years, civil society organizations in Brazil have been working to increase forestry transparency and the use of open data – data that can be freely used, modified and shared by anyone for any purpose – in the fight against illegal logging. A set of initiatives has been created which uses the available data to produce new analyses, solutions and tools to address this challenge.

There are currently three main types of data on Brazil’s forestry sector managed by federal and state agencies. The first is logging permits which detail the area, species and volumes authorized for logging as well as the identity of land owners and those responsible for forest management.

The second is timber transport, processing and trade data which shows the origin and destination of timber at each stage of the supply chain as well as the volume, species and values traded.

The third is land data which includes the location of conservation units, indigenous lands and private properties.

The first important step to make all of this existing data usable is to have it in a digital format. In recent years, federal and state governments have implemented digital systems for controlling logging. The National System for the Control of the Origin of Forest Products, SINAFLOR, launched in 2018, for example was an important step with 25 of the 27 Brazilian states adopting SINAFLOR either directly or indirectly by linking it to the control systems that they already had in place.

Another crucial aspect is the existence of a favourable legal framework for data transparency and accessibility for the forest sector and beyond. Some milestones in this regard can be highlighted. For example, the 2003 Access to Environmental Information Law stipulates environmental licences must be proactively disclosed while the Forest Code Law, approved in 2012, requires information on the forest sector should be public.

Furthermore, the 2011 Access to Information Law states that transparency should be the rule and secrecy the exception while, since 2016, all federal agencies have been mandated to contribute to the Brazilian Open Data Policy.

However, despite these advances, forest databases are only partially open in Brazil. Logging permits and the Forestry Origin Document, which contains data on timber transportation and trading, are accessible through SINAFLOR, but the system does not provide geospatial information and is not updated in real time.

In addition, the two states that are not using SINAFLOR are the two largest timber-producing states in the Amazon region: Pará and Mato Grosso. In Pará, transportation and trading data are not made available and logging permits are only released in PDF format.

Similarly, in Mato Grosso, despite recent advances, transportation and trading data are incomplete and not in an open format.

Furthermore, data on transportation and trading are not in the same format for all systems (SINAFLOR, Pará and Mato Grosso systems), requiring extensive filtering and standardization prior to integration and processing.

In this respect, transparency is currently limited by several factors: the incomplete availability of data, data that is not available in machine readable formats and a lack of integration between different systems. This all prevents access to existing data and means additional resources, and time, are required for accessing and processing it.

Despite these limitations, the opening up of data so far has already enabled some important and promising initiatives to emerge.

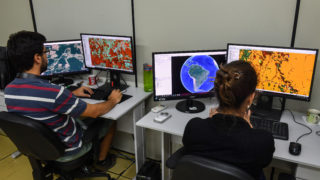

Imazon, a research-focused organization based in Pará, has developed a timber harvest monitoring system, SIMEX, which combines satellite images and data on logging licences to map logging activities in public and private lands and also identifies legal and illegal operations.

Imazon currently performs this analysis for the state of Pará and, according to its latest report (2017/18), 70 per cent of the logging detected in that period was illegal while 62 per cent of this illegality occurred in just five municipalities.

The NGO ICV also uses SIMEX to perform a similar analysis for the state of Mato Grosso. According to ICV’s latest report (2016/17), 39 per cent of the state's logging was illegal. Of the illegal logging that took place in conservation units, over half – 57 per cent – was concentrated in a single state park.

In 2017, another NGO, Imaflora, launched the TimberFlow Platform, which uses approximately 30 million data lines on transportation, processing and trade of timber to generate visual and numerical outputs on the forest sector. Besides capturing trade flows between Brazilian municipalities, the platform can reveal which species and products are commercialized the most and can generate analyses of the domestic supply chain of timber.

BVRIo has also developed the Timber Due Diligence system which enables buyers to find out about the risk of illegality of a given batch of wood. By combining satellite imagery with data on logging licences, timber transportation, environmental infractions and embargoes among other things, the system attributes a level of risk to each timber lot analysed.

These initiatives all demonstrate how data has enabled civil society to monitor the forestry sector more effectively in recent years - with benefits for businesses and enforcement agencies alike.

But so much more could be done. What changes are needed to leverage the full potential of open data for combating illegal logging and empowering legal and sustainable logging? There are three key recommendations:

- Making information available is not enough – it needs to be used. It is important that governments and companies start using the tools civil society has developed routinely. This does not always happen, either due to a lack of human and financial resources or due to an unwillingness to challenge the illegal activities in the forestry sector. Combined pressure from consumers, citizens and civil society can help in this direction.

- With more, and better, data much more can be done. Governments need to implement robust transparency and open data policies and practices ensuring adequate access to the different databases related to the sector. The different licensing systems for the logging, transportation and trade of wood need to be integrated and the environmental agencies which compile the data must be strengthened.

- There is plenty of room for collaboration. The initiatives presented here have complementary approaches. They also share common challenges with accessing, filtering, standardizing, processing and analysing large amounts of data. A greater exchange of experiences and integration between initiatives and organizations, therefore, could reduce costs and generate new analyses and applications of data.

With more use, openness and collaboration, open data will have a growing impact on forest conservation, the economy and the lives of local communities.

* Special thanks to Ana Paula Valdiones (ICV), Marco Lentini (Imaflora), Bruno Maier (BVRio), Danton Cardoso (Imazon) and Juliana Gil for the valuable conversations that contributed to the writing of this article.