Forest Voices: ‘I don't have a problem with logging companies: I just want them to log according to the law.’

Rodrigue Ngonzo is a leading expert in independent forest monitoring. In the first of a new series, he shares his story on the development of the approach, why it’s become a critical instrument in forest law enforcement and how international actors can get behind it.

‘The forest has always been a part of my life.’

‘I was born in Nanga-Eboko, a small town in Cameroon, surrounded by dense, tropical forest. But for many years it has been considered a hotspot of illegal logging.’

‘Some of the first reports released by Greenpeace about the ‘chainsaw criminals’ happened in my local area.’

‘I was born there and then grew up in Belabo – another small forest town in the eastern region of Cameroon.’

‘But, as time passed, I saw changes in the environment.’

‘The forest disappeared around the town. The climate became hotter. The rhythms of the rains changed.’

‘In the past, we would catch animals in front of our house, because we were so close to the forest. We used to play with pangolins when I was young – now a protected species in Cameroon – as we found them easily. Not any more.’

‘And there were lots of monkeys. So many monkeys. Now they have gone.’

‘As the forest disappears, the habitat of those animals also disappears, and they themselves then disappear.’

Image – A lumberjack at work in Cameroon. Sustainable, commercial logging within designated areas and in accordance with a suite of laws and decrees regulating its practice is part of the country’s strategy for development. Photo: Shutterstock.

‘My father worked in wood processing in Belabo but I felt it was better to work in forest protection. I don't have a problem with logging companies: I just want them to log according to the law and to fulfil their commitments to communities and the environment.’

‘So I decided to study forestry. I wanted to provide more opportunities for communities who use the forest for their own development.’

Today, Rodrigue is the president of the board of Forêts et Développement Rural (FODER) – a non-profit environmental organization based in Yaoundé.

Having begun in Cameroon, it has now expanded across the Congo Basin to work in countries including the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast, providing support to civil society organizations across the region.

‘My motivation really comes from my childhood,’ says Rodrigue. ‘The love of nature and biodiversity that I had when I was growing up.’

‘I want to see communities have a greater space for their voice, that they exercise more of their rights and that they have better opportunities to be involved in the sustainable management of their natural resources,’ says Rodrigue.

‘I am convinced that forests could be better managed and provide more benefits to both communities and to the government. But the government cannot succeed in meeting this goal without involving communities and civil society to support the work that they are trying to do.’

‘Communities have already been using forest resources sustainably [for millennia]. If they hadn’t, there would be no forests now.’

‘Their traditional practices show that they can manage forests in the right way. So my belief is that communities should manage the forests for their own development and to use the forest according to their own traditions.’

Building on these principles, Rodrigue and his colleagues at FODER have been helping to establish and develop an approach to forest governance in Cameroon in which communities are an equal partner through their involvement in independent forest monitoring (IFM).

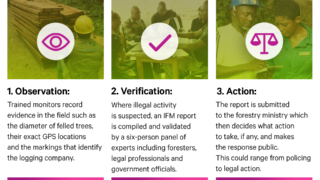

The approach provides the people who call the country’s forests their home with the tools to gather evidence of illegal logging and report it. It empowers local people and provides civil society organizations, government and international actors with direct information about how companies are using, or misusing, Cameroon’s forests.

IFM has evolved into a critical instrument in forest governance, providing the data and evidence necessary to strengthen enforcement of logging laws. ‘The observers, or people who are engaged with the process, feel more happy to engage in this new direction of forest monitoring,’ says Rodrigue. ‘They have made it like a second job in their communities. It has become a kind of vocation for them to protect the forest and their forest resources.’

Currently, Rodrigue and the FODER team have helped to put in place a network of 84 community-based monitors across the eastern, central, littoral and southern regions of the country, working with a network of both national and international partners.

Care is taken to make the monitoring process as accessible as possible and open to all. The initiative engages community leaders to help in this regard. Now, nearly a quarter of monitors are women.

Community members who take on the role of forest monitors are carefully trained to record logging activity and to send alerts upon encountering evidence of an illegal infraction by loggers in the forest.

Illegal activity might include a company without the rights to log in a specific area, not abiding by regulations or respecting environmental protections – for example felling immature trees – or causing damage to community areas.

Image – Independent forest monitors record the diameter of a felled tree to ensure it is within regulated limits and can use the markings to check the permissions of a specific company to log in that area. Photo: FODER.

Overall Cameroon has been making good progress to counter illegal logging over the past 20 years. Chatham House estimatessuggest that, since 2000, its proportion of illegal timber exports has fallen from almost half to a quarter in 2018.

Independent forest monitoring has played an important role in this. However, illegal activities remain widespread. Delays in the monitoring process have been one fact hampering progress explains Rodrigue. ‘There was too much time between the day when infractions were observed in the field to the day that the government, which is the law enforcer, was informed.’

It could be a matter of days, even weeks, for information to be collated and verified on the ground before being passed on to the authorities. Seeing the need to shorten these timeframes, Rodrigue’s team reached out to international partners to help.

Working with Rainforest Foundation UK, they helped develop a real-time monitoring system – ForestLink – which enables community observers to record information via a dedicated mobile phone or tablet app. And by using a satellite connection, it allows them to transmit that information quickly from wherever they are.

Images – The ForestLink system uses a bespoke app for mobile phones and tablets that allow community monitors to document and transmit evidence of illegal activity more quickly, via satellite link, from anywhere in the forest. Photos: Rainforest Foundation UK & FODER.

‘Now, the day the communities have observed something, is the same day we have that information,’ says Rodrigue.

‘They take the information collected – pictures, evidence, measurements and geographical coordinates – and they write what we call an IFM Report.’

Once the report is validated internally by a panel of experts – including foresters and lawyers – it will be sent to the government and then is made publicly available to all stakeholders.

This technological step forward has helped to revolutionize the IFM process by creating a network of live monitors from even the most remote communities and locations – and its efficacy has quickly meant it’s being taken up across the region.

‘Now ForestLink is being implemented by many countries like Ghana, the DRC and the Congo,’ says Rodrigue.

Through his work with FODER, Rodrigue played a pivotal role in the early stages of implementing forest monitoring in Cameroon. There is now a strong, collaborative network of IFM organizations across the Congo Basin including Observatoire de la Gouvernance Forestière (OGF) in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Brainforest in Gabon.

‘Making this information available and making people know what is happening is a very good strategy to discourage illegalities and to force the government to act,’ says Rodrigue. ‘Civil society is our watchdog.’

His colleagues at Citizen Voices 4 Change (CV4C) – a consortium of partners across the Congo Basin, and coordinated by the Centre for International Development and Training in the UK - also argue that forest monitoring should be seen as an extension of government enforcement efforts who might otherwise not have the resources required. ‘It is not there to compete with the government or to expose a government. It is there to complement a government,’ says Richard Nyirenda.

So far the evidence is that it’s doing just that. FODER state that out of 59 monitoring reports sent to the country’s forestry ministry from 2015 to 2019, acts of illegal logging were confirmed in 44 of them by the government.

Not that it always leads to action. ‘Law enforcement officers often don't have the power, they don't have material and they don't have enough means to verify infractions and to implement the law on the ground,’ explains Rodrigue.

But independent monitoring can also expose such shortfalls within law enforcement and help identify areas where additional resources are needed. It can also signal corruption and highlight where officials aren’t moving the monitoring process forward as they should be.

‘Many actors are involved in illegal logging, the private sector, some individual operators. But we also have the government itself or government agents, people who are supposed to be implementing the law, who are breaking the law on the ground. There is a lot of corruption,’ says Rodrigue.

Such corruption – as well as other aspects of illegality – is ever changing, says Serge Moukouri, a technical adviser with the Field Legality Advisory Group (FLAG) – a hub of IFM expertise based in Cameroon which helps to share knowledge and practice across neighbouring countries of the Congo Basin.

As he explains, the monitoring process needs to adapt to keep up with the changing nature of illegal activity. ‘Monitoring of logging activities in the field is just one area of focus. You have to monitor the entire chain – that is from a logging area, to transportation, processing and even exports in order to have a better understanding of what is going on.’

‘As one problem is identified, a different problem rises, and monitoring organizations have to adapt their methods and strategy so that, when they see there is a decrease in one type of illegal activity, they have to ask themselves what is happening so that they can understand how it is evolving.’

One such example they have witnessed in Cameroon is in the bidding process for forest logging titles– before logging even begins. Here, the location for a permit is changed by corrupt officials after it is allocated to a company – granting them access to land, often in a completely different area, that should not be logged.

With the sophistication and diversity of illegality growing, sharing expertise between countries is increasingly crucial. Though not always a straightforward task.

‘Coordination both within and among countries is not always easy,’ says Serge. ‘This is because individual organizations in each country are not at the same level. There is still a lot of work to be done before all the organizations have the same understanding of the monitoring process.’

But this difference can also be a strength: FLAG has spent time identifying organizations' technical skills so they are better equipped to help each other. ‘Mapping the competence of different organizations means they can exchange skills and has helped improve collaboration between countries.’

Despite the many challenges, the bigger picture in Cameroon suggests that forest monitoring is proving to be a powerful tool for bringing lawbreakers to justice. Fines on illegal logging in the country – issued as a direct result of IFM reports – totalled 72.5 million Central African Francs between 2016 and 2019 – equivalent to around £100,000.

Independent forest monitoring also helped to lead to the suspension of two companies in November 2019. A court found the companies guilty of unauthorized logging and ignoring technical regulations using reports by FODER and its partners as evidence in its decision. FODER’s investigation of one of the companies was prompted by a series of 38 alerts on the ForestLink platform by an independent forest monitor.

Meanwhile for communities, feeling more empowered enables greater follow up and identification of corrupt officials according to Robyn Stewart, real-time monitoring project coordinator at Rainforest Foundation UK.

‘The examples remain small in regards to the scale of the problem so far but they provide hope that, maybe one day, change – good, big change – can happen,’ adds Rodrigue.

As well as supporting the work of local governments and civil society organizations, forest monitoring can strengthen links with international partners and institutional actors. Information can be made available to bodies such as the World Bank, European Commission and the UN thereby enabling them to hold their partners to account.

‘Sometimes the illegality alerts come through the EU delegations. The community will send an email, or say, this is happening in our community and the EU will pass on that information. Then our partners will independently verify that information and write the report,’ says Dr Aurelian Mbzibain at CV4C. ‘So it's a two way process – we try and see this as a partnership.’

‘It helps a lot to have international support and recognition of IFM – and professional IFM work. It's very important,’ explains Rodrigue.

‘International actors and donors deal with the government for many other issues like health, education, elections, finances. They cooperate with our country on many other issues and we want them to provide political support to make sure that our government recognizes the work of IFM too.’

Rodrigue and the FODER team have also gone one step further, developing their independent forest monitoring approach and processes to win accreditation from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) – a body which works closely with the UN. This globally accepted third-party approval means the data garnered from IFM is recognized internationally as high quality.

‘This is also why we go through the quality management, certification process because you want to show the government that, all the work we are doing, we are doing it for the better management of forests and we are doing it with a higher level of objectivity and credibility so that there is no political issue behind it. It’s about making sure that forests are managed rationally,’ says Rodrigue.

Ultimately, Rodrigue’s goal is to have independent monitoring built into the country’s forest protection laws. ‘In Cameroon, there is no legal framework for IFM – there is no legal support for IFM in the forest code. We need that,’ explains Rodrigue.

‘But in the Congo, for example, they have succeeded in the latest forest reforms to make sure that IFM is provided for within the law. It’s the same case in the Central African Republic and their timber trade agreement with the EU.’

Joe Eisen, executive director of the Rainforest Foundation UK, also sees a future for real-time monitoring alerts being embedded more routinely within such EU trade agreements – or Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs) – and being used as a safeguard.

‘Where I see ForestLink going next is opening up this data to the likes of the European Commission for monitoring VPA agreements with producer countries,’ he says. ‘If in a given region, there's a number of verified alerts or evidence of non-enforcement and corruption, then they would be able to suspend the legality assurance certificate for example. It could also be a tool for monitoring new laws on imported deforestation and human rights violations in supply chains that are coming onstream.’

‘In the future, the forest monitoring process could be expanded to other sectors like mining and agriculture and used to track climate change,’ adds Rodrigue.

Image – Logs are transported away from a forest in Cameroon. Photo: FODER.

For Rodrigue, international influence can also be exercised to encourage wider support for independent monitoring in principle and as a fundamental means to make progress on good forest governance.

‘Global leaders should invite the government to see civil society organizations not as against them but as partners in the implementation of the legal framework and policies,’ he says.

‘They need ground monitors to report on what is happening in the forest, what is threatening forests and to monitor the systemic constraints that are against good forest governance on the ground.’

‘They need to be aware that without strong civil society organizations, and without strong independent monitors on the ground, the objective of reducing deforestation and forest degradation might not be achieved.’

‘The issues of forestry policy and forest management are intertwined with climate change. They all need to be put on the table of international dialogue.’

Image – A group of forest monitors learn how to use the real-time alert system ForestLink. Photo: FODER.

Independent forest monitoring is an approach that can bolster national efforts to improve forest governance, strengthen the rule of law and protect forests.

|

This new set of stories aims to draw attention to the critical importance of good forest governance for achieving global commitments on biodiversity, climate change and poverty eradication. Through personal perspectives on a variety of approaches from around the world, the series seeks to highlight some of the lessons learned so far and what further action will be needed at the UN’s COP26 climate conference in November 2021 and beyond.

------------

Produced by Unfold Stories.

Written by Molly Millar. Graphics by Alex Sommers. Direction by Simon Davis.

The views expressed in this article are those of the experts interviewed and not of Chatham House.