Forest Voices: To protect the land is to protect indigenous lives.

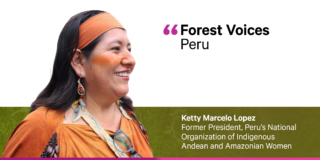

Ketty Marcelo Lopez is an advocate for the rights of indigenous women. In her native Peru, Ketty and her colleagues are campaigning for their rights to ancestral lands and for women to have an equal role in decision-making.

‘We are indigenous women in resistance.

‘We are a living culture, fighting for our identity, for our territories, and for the environment.’

Ketty Marcelo Lopez has made it her life’s work to give a voice to the voiceless. Born in the rainforest of the Peruvian Amazon, she is one of the country’s 3.2 million indigenous women and a lifelong campaigner for the rights of her community.

Since 2009, Ketty has been working with Peru’s National Organization of Indigenous Andean and Amazonian Women (ONAMIAP) – an organization campaigning for the rights of Peru’s indigenous women.

This is a battle increasingly being waged on one key front: land.

‘My mission and the mission of ONAMIAP is to combat climate change and ensure food sustainability for Peru’s indigenous peoples,’ Ketty explains. ‘And the foundation for all of that is land rights – encompassing everything is the fight to defend our territory.’

Peru’s indigenous peoples are stewards of some of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, with more than half covered in forests and more than 7,500 endemic plant species.

But these forests and their inhabitants are under threat as, without legal recognition, indigenous territories are vulnerable to land grabs by government and industry.

From 2001-20, the country lost 3.39 million hectares of tree cover and, in recent years, the government has leased more than 80 per cent of the Peruvian Amazon to oil and gas companies despite much of this land being inhabited by indigenous groups.

‘There has been so much logging going on, most of the forests have been cut,’ Ketty says. ‘The river is contaminated. There are fewer fish, and there is less food.

‘And now we are seeing the impact of climate change. The heat is brutal, we can no longer work the land for long before we have to stop and find shelter.’

Image – A landscape view of Chachapoyas, a town in the Peruvian rainforest. Photo: Shutterstock/ Framalicious.

For indigenous people such as Ketty and the women ONAMIAP represents, the impact of land grabs and deforestation has been catastrophic.

‘For our community, the land is everything,’ Ketty explains. ‘It is the place where our ancestors rest. It is the place where we build our identity.’

Because of this intimate relationship with the environment, the stakes for indigenous peoples are high. Ketty continues:

‘When we fight to protect the land, the forest, and the biodiversity – we also fight for our lives.’

Access to land is one of the most powerful determinants of human wellbeing.

People with secure access to land are less likely to experience hunger or poverty, enjoy better health outcomes, an enhanced status in the community, and improved quality of life.

This is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with land ownership recognized as fundamental to eradicating poverty and ending hunger, and important for gender equality.

Image – Over half of the land on the planet is indigenous and community territory. Photo: Rights and Resources Initiative.

Land rights are a critical element of forest governance. Secure legal backing of these rights empowers individuals and communities to protect their land and natural resources.

Omaira Bolaños, director of Latin America and Gender Justice Programs at Rights and Resources Initiative, explains: ‘When we give people legal rights, we equip them to better manage the forest and protect it from harm.’

But such rights are not universally recognized.

More than half the land on the planet is indigenous and community territory used and managed by up to 2.5 billion people. Evidence from Latin America shows forests within these territories are less vulnerable to deforestation and more effective carbon stores than the nearby state-run forests.

But only one-fifth of indigenous land is legally recognized. The failure to acknowledge communal ownership of land, the state’s desire to profit from natural resources, and complex land registration processes, all stand in the way of the recognition of indigenous land rights.

Without legal protection, indigenous lands are at risk of seizure by commercial and state interests. Omaira explains:

‘We see industry claim the land of indigenous people because their ownership is not legally recognized. There is nothing to tell them not to. They can easily go in and sweep away communities.’

Image – Indigenous women organize under ONAMIAP to campaign for their land rights. Photos: ONAMIAP

While indigenous land rights are often overlooked, indigenous women face additional challenges.

Women own less than 20 per cent of the world’s agricultural land and, although many countries have established targets to increase the number of land titles given to women, legal titling is only part of the solution. Addressing patriarchal customs and practices is also key.

Because women are often denied membership to community governance institutions, their interests are frequently not taken into account in decision-making processes, so the decisions taken may not reflect the particular ways in which women use land – such as the fact they tend to rely heavily on the commons.

Globally, there is a need both for more comprehensive protection of indigenous and other community lands as well as better representation of women’s interests.

In Peru, indigenous communities have the legal right to manage approximately 27 million acres of territory – around 16 per cent of the country’s total land. But a further 24 million acres are still without formal recognition.

Full title is only granted to agricultural land, not forest areas. All forests in Peru are state-owned so indigenous communities can only gain ‘usufruct’ rights – giving them the temporary right to use resources on the land.

Rights to agricultural and forest lands are granted to communities under the Native Communities Law passed in 1974. Although a communal approach to land titling is positive, it does risk negative consequences for women – particularly indigenous women – as they are under-represented in community institutions.

Sources: FAO, The gender gap in land rights / Landesa, The Law of the Land, Women’s Right to Land / World Resources Institute, Beyond Title: How to Secure Land Tenure for Women

According to a 2019 survey of indigenous communities in Peru, 43 per cent of men take part in community rule-making activities compared to just 22 per cent of women.

But the situation is improving in Peru and, over the past decade, ONAMIAP had several landmark achievements.

As a result of workshops and awareness raising programmes the group organized with indigenous communities, a number modified their statutes to increase the representation of women in their governance bodies.

ONAMIAP’s approach is to work with community leaders to raise awareness of gender issues and of women’s contributions to land and resource governance. This helps them gain leaders’ support to address these issues, establishing a basis for constructive community-wide discussions.

Working with community institutions and processes is an important principle for ONAMIAP to ensure they are reinforcing their autonomy rather than undermining it.

‘It was quite difficult at the beginning,’ Ketty says. ‘Because community leaders were reluctant to incorporate women's rights into their decisions. But we have helped to advance their views, and things are now more open.’ ONAMIAP has also led spokesperson training programmes which focus on building the leadership capabilities of indigenous women.

The programmes aim to equip women both to occupy governance positions within the community and to advocate for their rights more broadly within Peruvian society. Awareness of gender rights – and of the importance of women in forest and land governance – is low among many government officials in Peru.

This emphasis on community governance and leadership should be emulated more widely says Luis Felipe Duchicela, senior advisor for indigenous peoples’ issues at USAID: ‘National governments and the international community need to work alongside indigenous organizations and devote resources to the training and capacity-building of indigenous leadership.’

Image – ONAMIAP are working to build the leadership capabilities of indigenous women. Photo: ONAMIAP

ONAMIAP has also made progress at the national level. In 2016, it joined a national advisory committee advocating for indigenous interests in a major rural land titling project – a move which highlighted the importance of multi-stakeholder support for land titling.

The organization has since participated in national and international climate change discussions, raising awareness and understanding among policymakers of the particular needs and priorities of indigenous women.

But Ketty still has much more she would like to achieve.

'The work of ONAMIAP is to reform both the world outside and inside of the community,’ she says. ‘It's a constant fight to guarantee our rights. There’s always more work to do.’

Ultimately ONAMIAP’s goal is to securely enshrine indigenous land rights in law.

‘The state has had a policy of taking the land from the indigenous community,’ Ketty says. ‘Now they must guarantee legal security for our territories to ensure the historical continuity of our peoples.

Photo: The Center for International Forestry Research

‘We need to change the constitution to have clearer rules. We want a proper guarantee that indigenous lands will not be taken.’

Ketty wants to see Peru’s constitution revised to include full land rights for indigenous communities regardless of whether the land in question is agricultural or forested.

Under their proposed reforms, communities would no longer have to apply for usufruct rights but would automatically have legal possession of all territories traditionally occupied by indigenous groups.

ONAMIAP also want changes to the Law of the Right to Prior Consultation for Indigenous and Native Peoples, which says the government must consult with these communities about decisions that could affect their rights – such as the leasing of land to companies.

Enforcement of the law has proved haphazard, with consultations often not taking place or occurring only after a decision has already been made.

ONAMIAP want the law changed so the government would be required to not just consult indigenous communities but actively obtain consent. It is also calling for greater accountability and forest monitoring to ensure laws preventing land seizure are properly enforced.

Luis Felipe echoes this sentiment: ‘We need public policies that prevent external economic drivers from doing harm in indigenous territories – that means the use of free prior informed consent.’

Grassroots organizations such as ONAMIAP play a vital role in creating much-needed pressure on government. But they also serve an important function as educators and mobilizers within their own community.

'We must know who we are and we must understand our rights,’ Ketty says. ‘ONAMIAP helps to inform the indigenous people of their rights and empower them to defend themselves against any sort of threat.’

Ketty and ONAMIAP are also continuing to push for reform in community customs which discriminate against women.

‘Our community laws still don't really talk about women’s land rights, so we are trying to revise these laws,’ explains Ketty.

ONAMIAP’s experience demonstrates that, to protect the rights of indigenous peoples and the land they inhabit, change is needed at multiple levels.

As Omaira puts it: ‘The system needs to be willing throughout, from international, to national, down to local governments.’

But, as Luis Felipe explains, this change must be driven by indigenous communities with their interests at its core: 'When you have something that's strictly top down, it's not going to work. We need to engage, to empower, and to partner with indigenous peoples, and to foster an enabling political environment in the countries where they live.

Image – A meeting of indigenous Peruvian women. Photo: ONAMIAP

When asked what she enjoys most about her work, Ketty is quick to answer.

‘Sharing thoughts with other women and working together to look for solutions. We help each other to be strong, to be resilient.

‘Over time, I would like to reach more indigenous communities, to help sustain the soul of resistance among indigenous women.

‘Women’s voices are often not heard, so we are fighting to give women a voice.’

Secure rights to land are fundamental to enable indigenous peoples, and in particular, indigenous women, to continue their effective stewardship of forests.

- A well-designed legal framework is a prerequisite for the recognition and respect of land and resource rights of indigenous peoples. This must encompass tenure rights, processes for titling and establishment of the principle of free, prior, and informed consent. Legal reforms are needed in many countries and should be a priority for national governments, civil society, and the international community.

- Indigenous peoples need a good understanding of their legal rights, and the skills and knowledge to defend them, to help ensure the implementation and enforcement of the law. Civil society can play an important role in empowering indigenous peoples in this way.

- Multi-stakeholder support is important to facilitate the effective implementation and enforcement of laws establishing land rights. This requires continued efforts to raise awareness and understanding of the role of indigenous peoples in managing land and natural resources.

- Indigenous women face particular challenges because of gender discrimination, both within customary norms and institutions, and more broadly in society. Overcoming these requires a multi-pronged approach, with actions from community level through to the international level.

- Civil society has an important role in increasing awareness of gender issues in relation to land rights. When working with indigenous communities, it is essential to work in culturally appropriate ways to reinforce their autonomy.

- The provision of training and establishment of networks for indigenous women is of critical importance to support them in advocating for their rights, and to strengthen their participation in decision-making processes.

This new set of stories aims to draw attention to the critical importance of good forest governance for achieving global commitments on biodiversity, climate change and poverty eradication. Through personal perspectives on a variety of approaches from around the world, the series seeks to highlight some of the lessons learned so far and what further action will be needed at the UN’s COP26 climate conference in November 2021 and beyond.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Produced by Unfold Stories.

Written by Mary Cruse. Graphics by Alex Sommers. Production by James Lovage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the experts interviewed and not of Chatham House.