Decolonizing research across the North and South

Chiara Chiavaroli explains why North-South research partnerships around the world need to change.

The history of research is often influenced by colonial power relationships such as in the UK, the US and across Africa.

Breaking the legacy and establishing equitable North-South research partnerships is a challenge that has been increasingly addressed by institutions in the North yet rethinking research partnerships does not easily translate into different practices.

Research partnerships often follow a neo-colonial research model where projects are designed and managed in the North while institutions based in the South are delegated the task of data collection leading to a lack of access to decision-making by institutions in the South based on assumptions about their lack of capacity.

Moreover, project management is often based on a top-down decision-making model preventing institutions in the South from being involved with the decision-making process.

Similarly, the fact that institutions in the North manage most access to funds limits the opportunity of institutions in the South to provide a check and balance on important choices made during the life-cycle of the project.

Such a model fails to incorporate the knowledge, as well as the experience, of researchers in the South and limits the space for collective knowledge production.

Rewiring research partnerships into principles of equity is critically important. 'SDG 17 on fostering partnerships for sustainable development is at the heart of all of the SDGs,' says Thiago Kanashiro Uehara from Chatham House. Yet, the well-intended efforts of rethinking, and indeed decolonizing, them does not easily translate into different practices and this needs to be addressed.

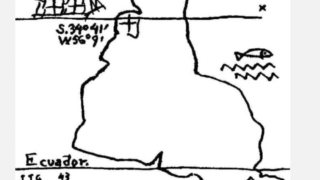

Here we reflect on the lessons that have been learnt in seeking to establish an equitable research partnership between Chatham House and institutions based in Indonesia (IPB University), Brazil (CEBRAP) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (CEPAS).

In Brazil, research has followed a similar pattern. ‘Physical domination, based on violence, took place when the country was a European colony,’ explains Ariane Favareto from CEBRAP.

‘Symbolic domination, even today, can be found in some [research] narratives based on a Eurocentric approach which has gone on to influence politics and even public action.’

'With this process, we have lost the opportunity of understanding better strategies [such as] the knowledge of indigenous people.’

In the case of Indonesia, Damayanti Buchori from IPB explains how the history of the country, which was colonized by the Dutch for 350 years, has affected how Indonesian researchers interact with their international collaborators.

‘The history of colonization has left remnants of insecurity [among] Indonesian researchers,’ she says. 'But the situation has greatly improved with a younger generation of researchers who possess more confidence [on the international stage].’

'International collaborations are still commonly set up by countries in the North although, in some cases, the processes have become much more inclusive.’

The Forest Governance project at Chatham House in the UK has not been exempt from such dynamics too. From the beginning, Chatham House has been in charge of managing the budget for the project as well as relationships with the funders. Indeed, avoiding tokenism has meant acknowledging colonial power relationships at every step which has included clearly defining which decision-making spaces were left open to partners.

Forming a collective definition of what ‘participation’ means for the project, for example, was essential for translating the rhetoric of ‘inclusive’ and ‘equitable’ research partnerships into a reality of knowledge production.

Furthermore, being able to define research methodologies and select case studies within the project was considered particularly important by partners as a pathway towards independent thinking.

In addition, thinking about communication practices was crucial to preventing indirect pressure on non-English speaking partners. For example, an important takeaway of the Forest Governance project has been failing to prioritize the different linguistic needs of research partners which can exclude those with a low level of English. Therefore, assigning more funds for translation is vital to strengthening inclusivity.

In parallel, designing research outcomes relevant to the different national contexts of all of the partners involved is crucial in order to be accessible to a diversity of national stakeholders while rethinking publication practices and public engagement strategies to adapt them to different national contexts is also essential for producing knowledge that can feed into national debates.

‘It has been thought-provoking and, at times, challenging to address these issues,’ says Alison Hoare formerly of Chatham House.

‘What has become apparent is that attitudes related to power permeate through every aspect of a project, from project design and decision-making, to communication.’

But transparency is the key she says. ‘For the project, acknowledgement of what the power relations were [was important].’

Beyond the rhetoric of inclusivity and equity, however, attempting to establish participatory research partnerships teaches us that they need to be slowly co-constructed through collective discussions and by making power relationships explicit. For example, creating safe spaces and confidential channels for partners to bring criticism to leading institutions, and leading institutions to be willing to take action on such criticism, is crucial.

Implementing such changes may require questioning the idea of efficiency. But, avoiding tokenism, and creating research partnerships which are truly inclusive and equitable, requires a willingness to question institutional and personal practices, investing time, human and material resources and making concrete changes in the construction of new collaborations.